The genre term ‘platformer’ infers a style of gameplay that requires the player or players to reach a defined goal by moving across static or fixed platforms. It was not until the early 1980s with the introduction of Donkey Kong (Nintendo 1981) that the modern definitions of platformer ‘rules’ were defined, in which the player must reach the goal by jumping (Bycer 2019, pp. 5-6). Metroidvania is a sub-genre of action-adventure platforming games and places a strong emphasis on backtracking and exploration. The term is a portmanteau of Super Metroid (Nintendo 1994) and Castlevania: Symphony of the night (Konami 1997), which are the two games from their respective series which have defined the genre (Cossu 2019). Such games can best be described as an exploration game with a lack of linearity and whilst there is no formal definition of what constitutes metroidvania, games in this sub-genre often employ subtle tones of despair and desperation to overcome unique limitations and boss style fights (Hart 2019, p. 20). This essay will present a discussion and examples of the base mechanics and playstyles typical of metroidvania games, along with a comparison to traditional platformers.

Base mechanics and playstyle

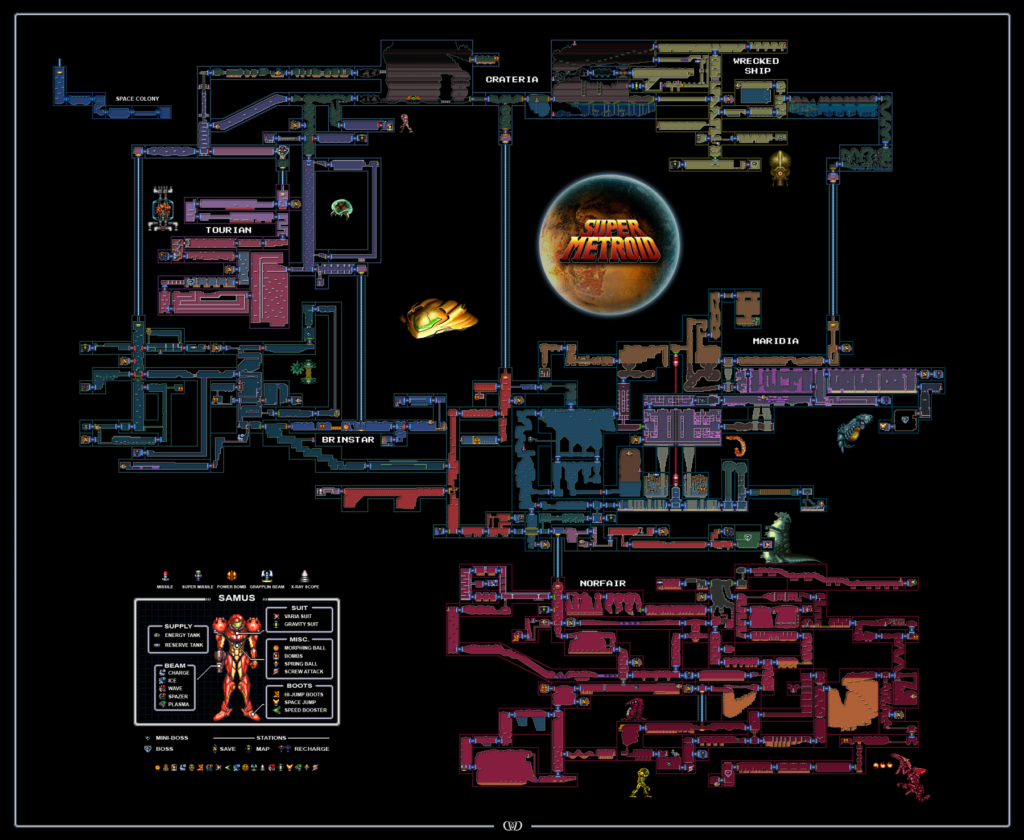

There are a number of elements and base mechanics that characterise metroidvania games. A particular focus of the genre is the exploration of complex structures which often requires particular items or move-sets to be unlocked over time to progress, which often means backtracking through levels or barriers (Cossu 2019). An example of the way in which this can be done is through the acquisition of abilities such as the double jump in Ori and the will of the wisps (Xbox game studios 2020; Figure 1). An added benefit of this backtracking is that it allows for the reuse of areas and assets to include hidden challenges and items/power-ups in an area that a player is already familiar with. This nonlinear progression is often apparent to the player through the map screen and minimap, both common features in metroidvania games (Figure 3; Figure 4).

Unlike traditional platformer games such as Mario Bros. (Nintendo 1983) and Donkey Kong (Nintendo 1981), where gameplay generally moved in a left to right motion to complete the level, metroidvania games do not suffer from linear based storytelling or level design. With the arrival of the original games in the Metroid and Castlevania series, players were given the ability to explore the platform in any style they wished. In order to circumnavigate the risk of players stumbling upon the exit to the level or game the mechanics of roadblocks/barriers were introduced into gameplay, thus forcing players to explore each different area of the map. An example of the emphasis placed on these roadblocks in metroidvania is the requirement of different items/weapons in Super Metroid (Nintendo 1994; Figure 2) to unlock doors and progress through the stages of the game.

Figure 1. Ori and the will of the wisps

Figure 2. Super Metroid Green Door

Other genre influences on metroidvania games

As a whole, metroidvania games have been influenced rather little by alternative genres, however, minor nuances can be identified over time since the development of larger games. For example, core RPG elements that allow for character development and level progression, along with the need for players to develop and memorise strategies to overcome areas in unique ways as more procedurally generated levels are created, can be seen in metroidvania games such as Hollow Knight (Team Cherry 2017) and Dead Cells (Motion Twin Playdigious 2018). Despite this, it can be observed that since the inception and introduction of metroidvania in the mid 90s the sub-genre has seen little divergence from the core mechanics that epitomise the gameplay style. This notion is supported by a presentation made by Koji Igarashi (2014), one of the forefathers of metroidvania, at the Game Developers Conference in which he states that the sub-genre in general has inherited traits from action and platformer based games, with little need to draw from other genres.

Metroidvania vs. adventure game mechanics and playstyles

The way in which metroidvania games differ to more traditional adventure games can be defined as a ‘blend of rewards of access and reward of facilities’ (Hart 2019, p. 9). One of the key differences of this sub-genre is that players are taught how to overcome obstacles. Rather than giving the player tools from the outset, many metroidvania games require the player to traverse and explore the map to overcome the obstacle. Another point of comparison is item acquisition and subsequent use. Two games which provide an excellent comparison of these approaches are The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (Nintendo 1998) and Metroid Fusion (Nintendo 2001). The Ocarina of Time style of item acquisition requires the player to navigate through challenges within a dungeon. The items are then used to complete the remainder of the dungeon and to defeat the boss. After the completion of the area, the game utilised the acquired dungeon item in a more limited capacity throughout the rest of the game. Conversely, in Metroid Fusion, items are not gated behind bosses but rather found through exploration of the game world. These items are then used to unlock more of the world allowing for further exploration and in turn, more items. The player uses the item through all stages of the game and is only gated by not having the item through obvious blockades made by the developers, such as breakable blocks or coloured doors that require certain weapons to open.

Conclusion

This brief essay has presented a discussion on what characterises the metroidvania sub-genre and the way in which the base mechanics and playstyle differ from more traditional platform games. In particular, it highlighted the divergence from linear progression in traditional adventure and platform games to backtracking and item/ability acquisition. Additionally, the emergence of more recent award-winning games such as Hollow Knight (Team Cherry 2017) and Dead Cells (Motion Twin Playdigious 2018), have provided a way for players to be eased into the sub-genre without the games difficulties often experienced in earlier games series such as Super Metroid and Castlevania.

Figure 3. Castlevania Sympony of the Night map

Figure 4. Super Metroid Map

References

- Bycer, J 2019, Game design deep dive: Platformers, CRC Press, Boca Raton.

- Cossu, S 2019, Game development with GameMaker Studio 2: Make your own games with GameMaker Language, Apress, Berkeley.

- Hart, J 2019, Backtracking: An Ecological Investigation to Contextualize Rewards in Games, Doctoral dissertation, Northeastern University.

- Igarashi, K 2014, There and Back Again: Koji Igarashi’s Metroidvania Tale, Game Developers Conference.

- Konami 1997, Castlevania: Symphony of the night, video game, PlayStation, Konami.

- Motion Twin Playdigious 2018, Dead Cells, videogame, Microsoft Windows.

- Nintendo 1981, Donkey Kong, arcade game, Radar scope, Nintendo.

- Nintendo 1983, Mario Bros., arcade game, Nintendo.

- Nintendo 1994, Super Metroid, video game, Super NES, Nintendo.

- Nintendo 1998, The legend of Zelda: Ocarina of time, video game, Nintendo 64, Nintento.

- Nintendo 2002, Metroid fusion, videogame, Game Boy Advance, Nintendo.

- Team Cherry 2017, Hollow Knight, video game, Microsoft Windows, Team Cherry.

- Xbox Game Studios 2020, Ori and the will of the wisps, video game, Xbox One, Xbox Game Studios.